Comics as a medium intersect frequently with conversations about disability in popular culture. From Japanese manga to Sunday cartoon funnies, comics portray those within different disabled communities through a spectrum of portrayals that range from considerate to problematic. Superhero comics epitomize this intersection; as comics scholars Josè Alaniz and Scott T. Smith explain, “the figure of the superhero itself has become a trope for considering issues of ability and disability in the culture at large” (Uncanny Bodies 1). As such, a thorough discussion of depictions of sound in comics necessitates an examination of disability representation, particularly in the areas of aural and visual impairment. Therefore, this section focuses on the intersection of disability and sound in three main areas. Because sound in comics possesses many communicative purposes, the first section extends that idea of communication and explores the depiction of sign language as a form of communication for those that are deaf and hard of hearing. The second area covers sound depiction in comics about deafness and those that are hard of hearing, particularly how sound is modulated to emulate the experiences of those within the disability community. The final section examines audio-based comics as an alternative to visual comic books for those that are visually impaired.

Hearing Impairment

These four comics are among the most popular comics that depict deafness. I Hear the Sunspot and A Silent Voice are two Japanese manga, while Hawkeye and Echo are popular Marvel Comics superheroes that are deaf and hard of hearing. These comics also offer additional social commentary beyond depictions of disability by delving into its interaction with other social issues, such as workplace discrimination and familial abuse.

I Hear the Sunspot: Limit Vol. 1, “Chapters 1-3”, 2017

Author: Yuki Fumino

Publisher: France Shoin

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Bato.to”

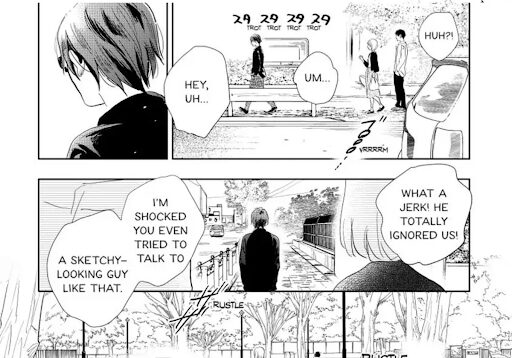

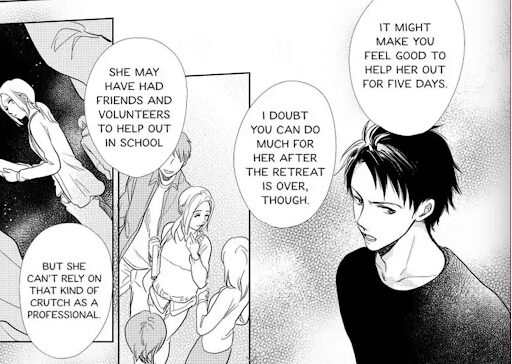

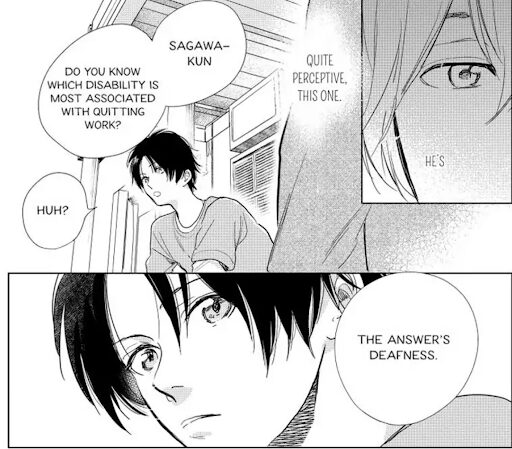

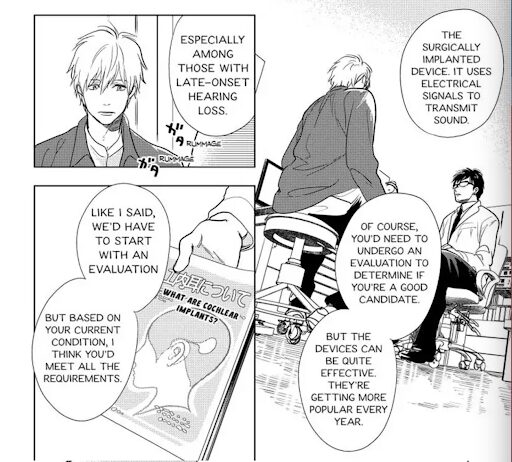

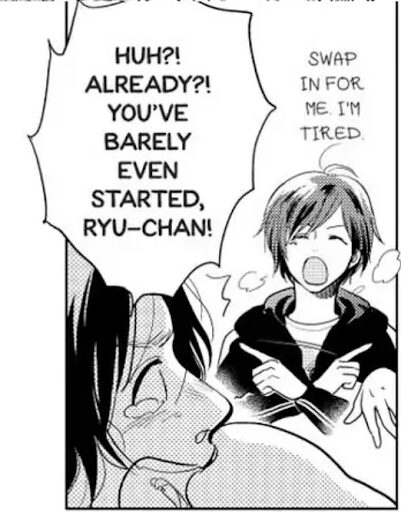

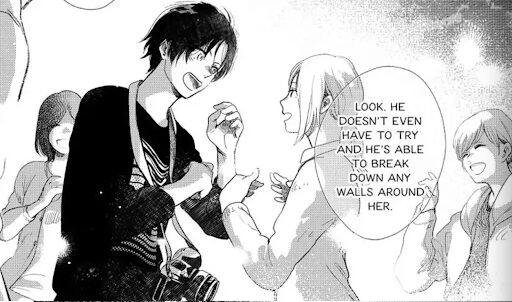

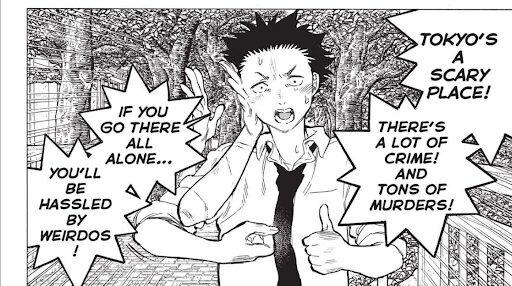

This manga centers around a college-aged student named Kohei, found in the first and upper-most image in a black coat and walking past a crowd that calls him “sketchy,” and his struggles with sudden hearing loss at school and in the workplace. His boyfriend, Taichi, supports him as he learns to accept himself and his life as he becomes deaf. Taichi also encounters ableism in the workplace, as evidenced by the second image, which involves Taichi confronting a boss that told him that he is not allowed to use sign language to communicate with a new employee that is deaf because she must learn to not use sign language as a “crutch” in her profession. Social themes covered in this manga include disability in sports, ableism in professional and educational settings, refusal of accommodations, and controversies over cochlear implants for those in the deaf and hard of hearing community. For example, in the third image, Taichi mentions that deafness is the disability most associated with quitting work, which draws attention to workplace inaccessibility and inequality. Likewise, the last and lowest image depicts Kohei learning about cochlear implants and the reasons why those that are hard of hearing might consider wearing them.

A Silent Voice, 2013

Publisher: Kodansha

Author: Yoshitoki Oima

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Mangakakalot”

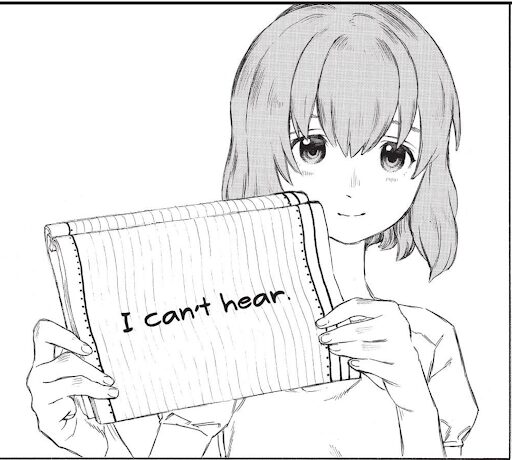

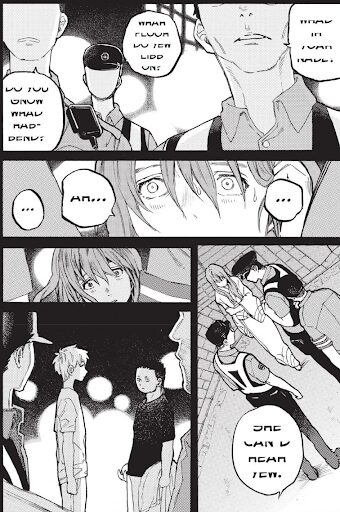

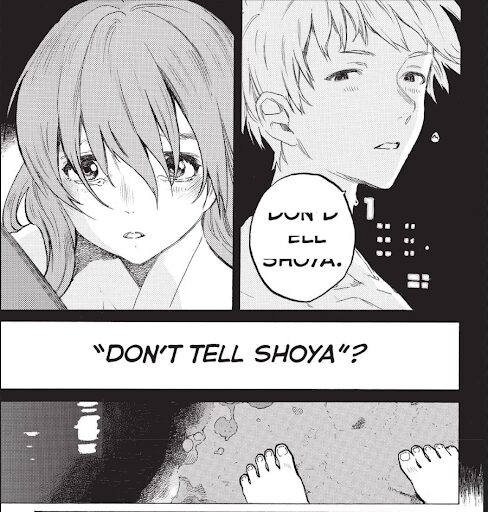

A Silent Voice follows Shoya Ishida, a school bully, and Shoko Nishimiya, a deaf student in Shoya’s class that communicates with her peers by writing on pieces of paper. As the second image from the top indicates, Shoya begins to bully Shoko as soon as he learns about her disability by yelling near her ear and getting other members of the class to join him. For instance, in the third and lowest image, he convinces his friends to make loud barking noises so that they can make fun of her when she cannot hear them. His bullying reaches the point where he takes out Shoko’s hearing aid, and Shoko feels so unsafe and unwelcome at the school that she decides to leave. When Shoko decides to return to school several years later, Shoya attempts to make amends and rectify his ableist tendencies by becoming friends with Shoko. The manga explores their struggle to become friends as well as Shoko’s residual trauma from her youth. Social themes and commentary permeate the story, particularly in the areas of inclusive classroom environments, peer pressure, and mental health for young adults. While this manga addresses these issues, there are still some problematic depictions of disability. For instance, Shoya’s lack of hearing is visualized through the onomatopoeia “Blah Blah Blah” from the lowest image, which inaccurately represents deafness because the word implies a connotation of ignorance and suggests that she may be disregarding them when in reality she cannot hear them.

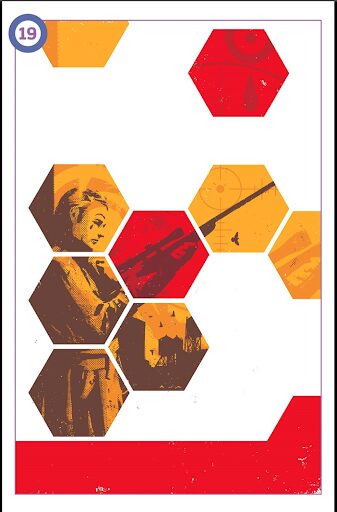

Hawkeye, Vol. 4 #19, “The Stuff What Don’t Get Spoke,” July 30, 2014

Writer: Matt Fraction

Penciller and Inker: David Aja

Colorist: Matt Hollingsworth

Letterers: Chris Eliopoulos and David Aja

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

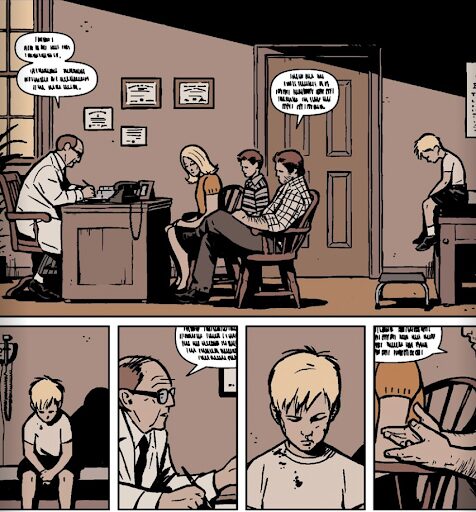

Perhaps one of the most well-known depictions of hearing loss in comics is Hawkeye #19. Clint Barton/Hawkeye’s status as an Avenger and the prominence of Marvel Comics in general means that this superhero has garnered lots of attention for this particular storyline in which Hawkeye loses his hearing as a result of an injury. Hawkeye’s hearing loss originated in the 1980s, but his disability was ignored in many subsequent issues. As a result, Fraction and Aja created this issue of Hawkeye to address his disability in a fully-realized run of the series and give both his disability and those within the deaf and heard of hearing communities the consideration that they deserved (Uncanny Bodies 157). This first image is the issue cover of Hawkeye #19, and the second image from the top features the first few panels of the comic, where a doctor writes about Clint Barton’s diagnosis of potential hearing loss. Lastly, the third and lowest image depicts “CLINT” spelled in American Sign Language, which becomes a prominent form of communication in the issue. In addition to the social commentary on disability, this article also tackles the topic of abuse because it is revealed that Barton once lost his hearing as a child due to physical abuse from his father.

Daredevil: The Man Without Fear #51, “Echo: Part 1,” November 2003

Writer, Artist, and Colorist: David Mack

Letterer: Cory Petit

Publisher: Marvel Comics

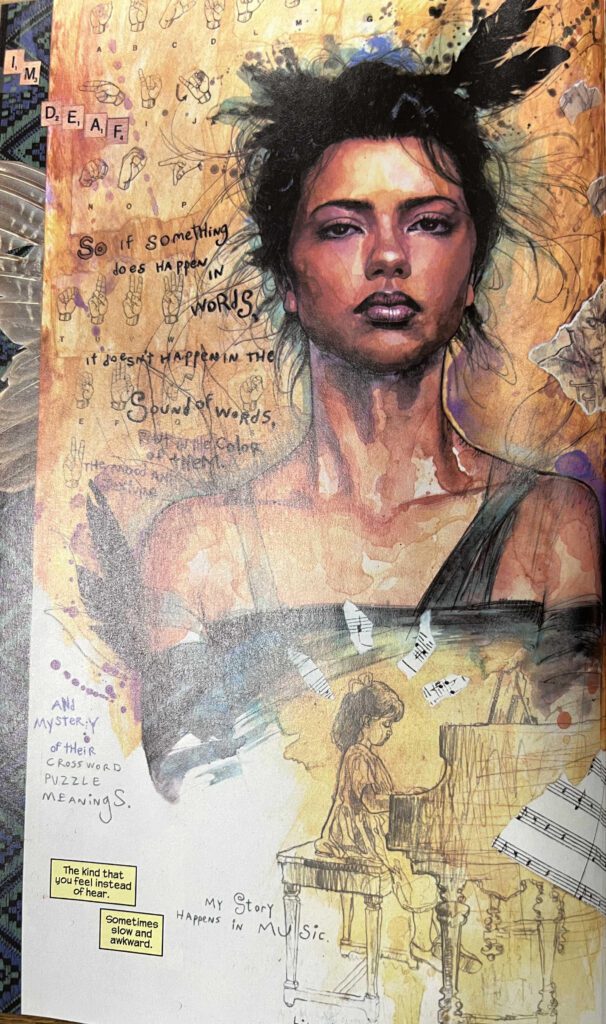

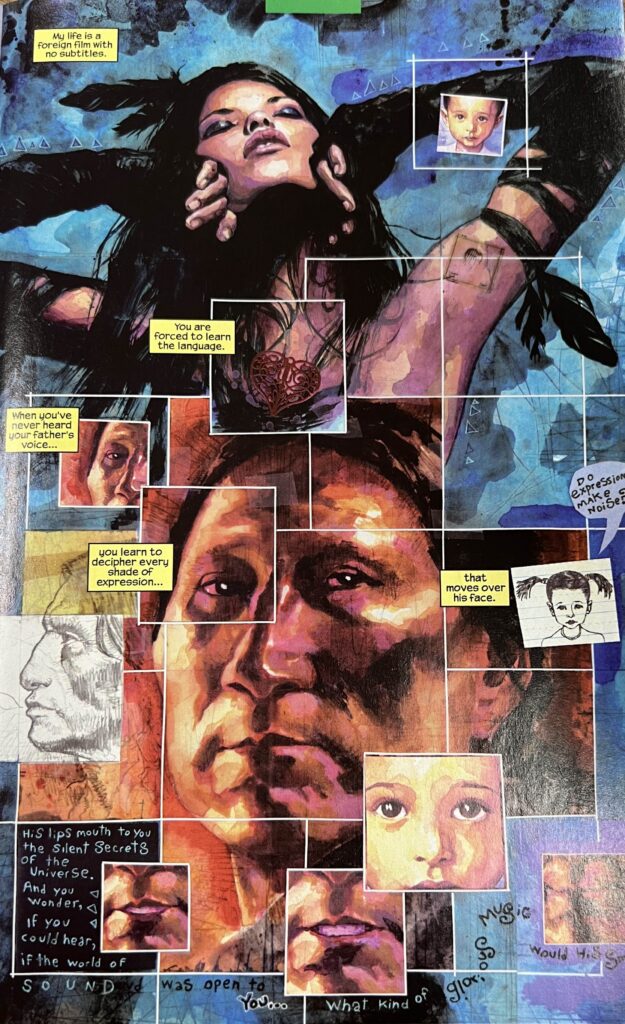

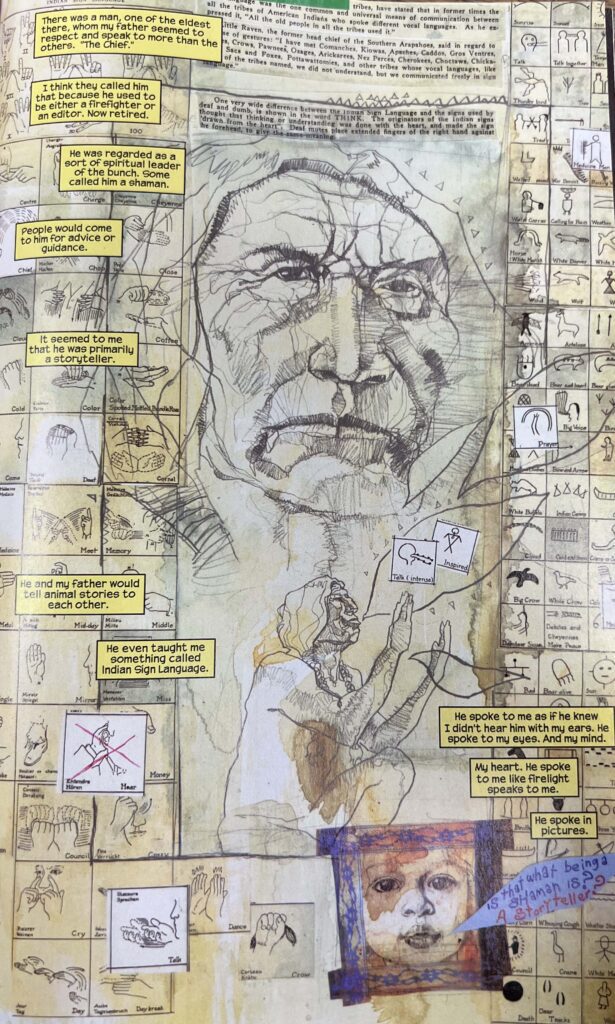

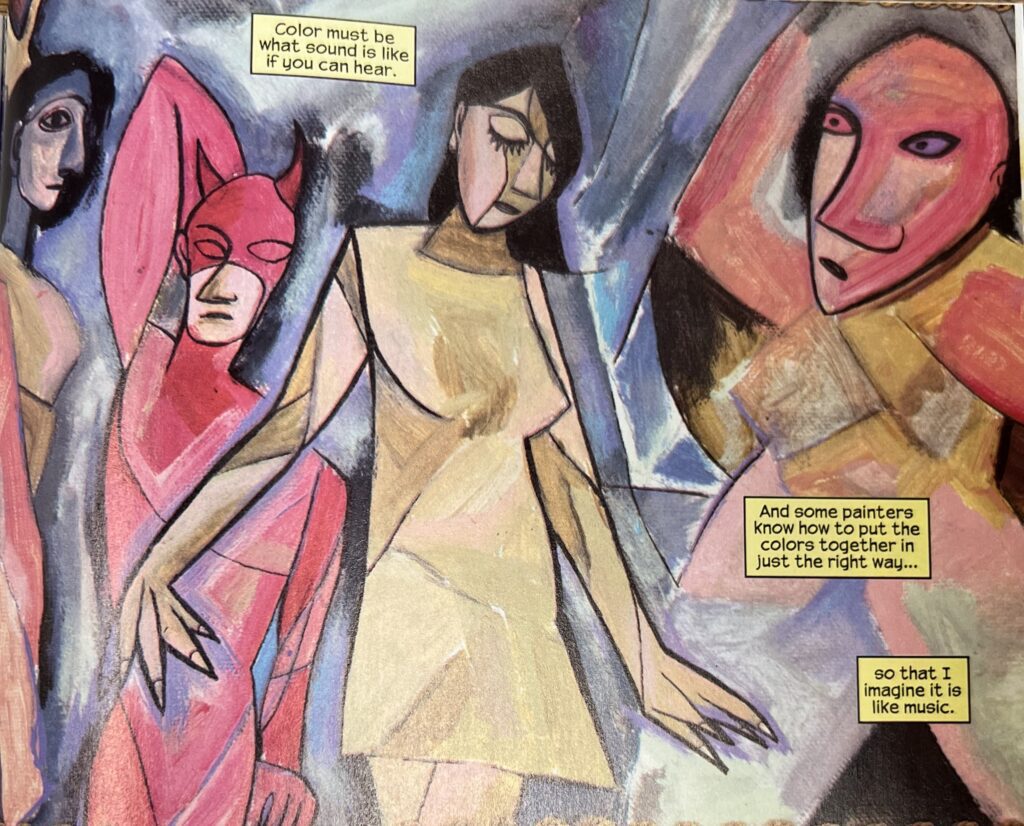

Maya Lopez, otherwise known as Echo, is perhaps the most popular deaf superhero. Maya is Native American and a member of the Cheyenne Nation, from which she learns the sign language of her community. She also possesses remarkable lip-reading abilities and a talent for visual art. She has her origins in the Daredevil franchise, and “Echo: Part 1” is the first time that her character and backstory are fully explored within this series. This issue features limited dialogue and few other depictions of diegetic sound; instead, it is told entirely through narration and images, such as in the upper image. However, sound is still a prevalent theme in the comic and is represented through images such as sheet music and her playing the piano. The most direct depiction of sound is infrequent speech bubbles, such as in the lower image, in which Maya asks her father what certain objects and concepts sound like. These conversations illustrate her trusting relationship with her father, which has significance to the plot later in the series. In terms of her experience as a deaf person, Maya describes how she perceives sound at the beginning of the comic through the line “if something does happen in words, it doesn’t happen in the sound of words, but the color of them.” This notion of color becomes a foundational aspect of Maya’s perception of the world, and she often uses artwork to express her inner thoughts and feelings. In addition to addressing deafness, Echo comics also explore the intersection between race, gender, Indigeneity, and disability.

Sign Language

Several depictions of sounds in comics fall under the category of communication, such as speech bubbles for dialogue or singing songs to an audience. However, these verbal forms of communication exclude those who are deaf or hard of hearing. As a result, comics about these forms of disability opt for a different form of communication depiction, namely sign language. While sign language depictions differ from speech and lyric bubbles, sign language can also sometimes adopt similar visual features as their verbal communicative counterparts.

I Hear the Sunspot: Limit Vol. 1, “Chapter 3”, 2017

Author: Yuki Fumino

Publisher: France Shoin

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Bato.to”

In I Hear the Sunspot, words communicated through sign language adopt a different indication of words than a speech bubble. The words are in a different font to show that a new form of communication is being visualized, which is similar to when the font of the comic changes when spoken dialogue shifts from speaking to singing. Likewise, instead of positioning the words within a speech bubble, they exist unframed. Hand gestures and motion lines also accompany these depictions of sign language to provide a pictographic representation of this form of communication.

Daredevil: The Man Without Fear #51, “Echo: Part 1,” November 2003

Writer, Artist, and Colorist: David Mack

Letterer: Cory Petit

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Page 15

On this splash page, Maya describes her experience learning sign language from a respected man in her Indigenous community. He teaches her “Indian Sign Language,” which is visualized in a collage behind the narration text bubbles. There is also an image of him communicating with hand gestures, and an elongated elliptical shape akin to a speech bubble juts from his mouth and contains Native American pictograms. Such a depiction emphasizes the fact that he communicates through an Indigenous sign language as opposed to American Sign Language. Maya recalls that “he spoke in pictures,” which reinforces her character as someone who comprehends sound through a visual lens.

View More Examples of Sign Language

I Hear the Sunspot: Limit Vol. 1, “Chapter 3”, 2017

Author: Yuki Fumino

Publisher: France Shoin

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Bato.to”

Sign language is framed at the forefront of this panel from I Hear the Sunspot. In this scene, Taichi and his coworker communicate animatedly through a series of gestures and facial expressions. Their hands occupy the center of the panel and all of the figures are turned toward their hands, further underscoring the importance of sign language in their discussion. In this panel, their words are not indicated, unlike other pages of the manga that provided the translation, so the audience serves a bystander role in which they are not privy to the conversation because they cannot understand the gestures. Such a position of the audience could be a form of social commentary that asks viewers to critically think about the communication barrier that exists between those that use sign language and those who cannot understand it.

Hawkeye, Vol. 4 #19, “The Stuff What Don’t Get Spoke,” July 30, 2014

Writer: Matt Fraction

Penciller and Inker: David Aja

Colorist: Matt Hollingsworth

Letterers: Chris Eliopoulos and David Aja

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

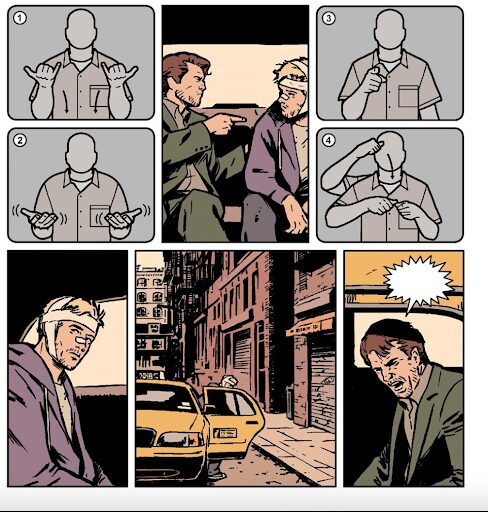

Page 4

Hawkeye #19 features sign language in two forms. First, the characters themselves, such as Clint Barton and his brother Barney in this scene, use sign language when communicating with one another, and the panel selects single parts of these conversations to visualize. At the same time, the conversations have sign language “subtitles” that explain in more detail the exact signs that they use. However, the meaning of these signs is never explained in alphabetic words, so audiences that are not fluent in sign language cannot understand their full conversation. The intention behind this format is to construct for audiences the same sense of frustration and incoherence that deaf and hard of hearing people experience in situations where sign language or other inclusive forms of communication are not used in order to create awareness of these struggles. As comics scholar Naja Later summarizes, the need to “use context, inference, and guesswork to decipher the narrative” in Hawkeye #19 “is striking in how it draws attention to the disabled experience of deafness in a Hearing world, and it does so by positioning inaccessibility as a design flaw” (Uncanny Bodies 149).

Hawkeye, Vol. 4 #19, “The Stuff What Don’t Get Spoke,” July 30, 2014

Writer: Matt Fraction

Penciller and Inker: David Aja

Colorist: Matt Hollingsworth

Letterers: Chris Eliopoulos and David Aja

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

Page 18

At the end of Hawkeye #19, Hawkeye communicates with a crowd of people that he has temporarily lost his hearing but that he will continue to fight for them. The speech, given through sign language and translated through his brother Barney, ends with a commitment to stand together, with Clint signing the word “we.” This word is then repeated by the crowd, which Clint understands by reading their lips. Finally, Barney says the word, and it is depicted in a final form of communication, which is the spoken word. Put together, one word is expressed in three different ways, but all of the people present still comprehend the meaning behind it. Such a section could be comment on the need for inclusive communication practices because it demonstrates the benefit of spaces that are created so that all people can understand one another.

A Silent Voice, “Chapter 21,” 2013

Author: Yoshitoki Oima

Publisher: Kodansha

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Mangakakalot”

Page 133

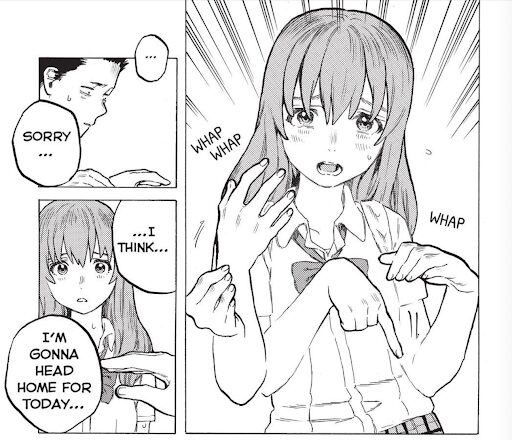

When Shoko and Shoya first reunite, Shoko tries to communicate using sign language, but as Shoya’s look of disappointment conveys, he cannot understand her. This visualization of sign language contrasts other depictions because it includes the onomatopoeia “WHAP” to indicate the sound of her hands moving in the air. In addition, the motion of her gestures is illustrated through the presence of multiple copies of her hands, each performing a different sign. As Scott McCloud contends, this idea of “multiple images of the subject” serves to “involve the reader more deeply in the action” (Understanding Comics 112). In this case, the audience is drawn to the different positions of Shoko’s hands, which underscores the fact that she is communicating through them.

A Silent Voice, “Chapter 59,” 2013

Author: Yoshitoki Oima

Publisher: Kodansha

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Mangakakalot”

Page 126

One way that the progression of Shoya and Shoko’s relationship is conveyed in this manga is through Shoya’s growing fluency in sign language. Whereas he was once unable to read her signs, towards the end of the manga, he can communicate with her more easily. This series of panels features both of them speaking through sign language; Shoko’s hands are framed as the only two objects within the last few panels, which demonstrates the centrality of her gestures in this conversation. An additional aspect of this series of panels in relation to sound is the translation of the conversation for those that are not fluent in sign language through Shoya’s dialogue. He states her signed words out loud as a comprehension check for himself, but the dialogue is also a vessel for audiences to translate her signs into spoken words.

A Silent Voice, “Chapter 59,” 2013

Author: Yoshitoki Oima

Publisher: Kodansha

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Mangakakalot”

Page 126

In this panel, Shoya expresses his frustration with Shoya’s decision to move away through a series of explosive bubbles that mimic a spiky word balloon. These bubbles translate Shoya’s signs into written words for the audience. The intention behind this particular shape of the bubbles could perhaps be the same reason for including them in general: the benefit of those that are unfamiliar with sign language. These shapes emulate common comic characteristics, which creates a sense of familiarity for audience members, many of whom are more likely have a stronger understanding of comic styles than sign language. The irritation in his statements is reinforced through the wide arc of his motion lines around his arms, his perspiration, and his angry facial expression.

Sound Modulation

Several comics about those that are deaf or hard of hearing visualize sound differently than other comics. One of the most common ways to modulate sound in these comics is to visualize dialogue as “asemic,” which comics scholar Dr. Barbara Postema defines as a style of writing where words possess no semantic or legible value. These changes in depiction reflect the differences in sound perception for those within those disabled communities in order to build empathy and understanding between the audience and the characters in the narrative that experience sound in those ways.

Hawkeye, Vol. 4 #19, “The Stuff What Don’t Get Spoke,” July 30, 2014

Writer: Matt Fraction

Penciller and Inker: David Aja

Colorist: Matt Hollingsworth

Letterers: Chris Eliopoulos and David Aja

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

Page 1

Hawkeye #19 introduces vocal and sound modulation early on in the narrative. In his series of panels, Clint Barton perceives the conversation between his doctor and parents as a jumble of lines that resemble words but possess no comprehendible value, making them asemic in their visualization. While they are still within speech bubbles, the dialogue is lost to both Clint and the audience; as a result, the audience adopts the perspective of Barton and grapples with the same sense of confusion and loss that he experiences, causing them to sympathize with his situation and, by extension, the experience of those in the deaf and hard of hearing community with similar perceptions of sound.

I Hear the Sunspot: Limit Vol. 1, “Chapter 2”, 2017

Author: Yuki Fumino

Publisher: France Shoin

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Bato.to”

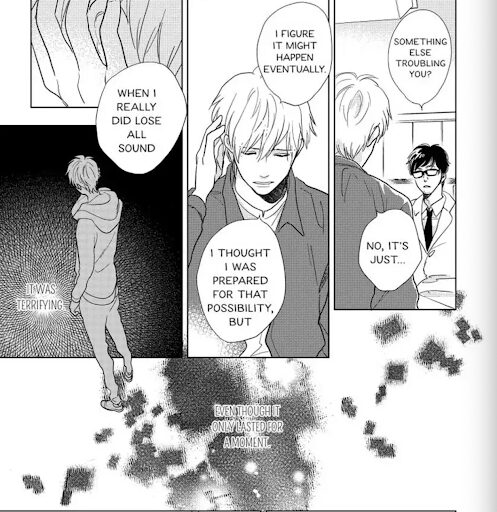

When Kohei meets with his doctor to discuss the progression of his learning loss, he reflects on the most recent time in which he “lost all sound.” This series of panels visualizes this reflection through a cross-hatch of black lines that evoke the sense of a void, as well as a pattern of nebulous blocks that float away from a darker, larger center abstract shape. On this page, the modulation of sound is not depicted in an aural sense but rather a psychological one, with Kohei mentally visualizing the fears and anxieties that he possesses about losing his hearing. This particular depiction of the loss of sound is unique because it implies that sound is light and a lack of it is dark, which displays the interplay between these two senses.

View More Examples of Sound Modulation

Hawkeye, Vol. 4 #19, “The Stuff What Don’t Get Spoke,” July 30, 2014

Writer: Matt Fraction

Penciller and Inker: David Aja

Colorist: Matt Hollingsworth

Letterers: Chris Eliopoulos and David Aja

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

Page 2

Whereas Hawkeye’s youth experiences visualized hearing loss as a series of indiscriminate lines, his hearing loss as an adult is expressed with speech bubbles that are completely blank. Such a shift could demonstrate an increase in the level of lost hearing that he experiences. This lack of understanding is reinforced by Barton’s facial expression of confusion in the third panel after seeing his brother attempt to speak with him.

Hawkeye, Vol. 4 #19, “The Stuff What Don’t Get Spoke,” July 30, 2014

Writer: Matt Fraction

Penciller and Inker: David Aja

Colorist: Matt Hollingsworth

Letterers: Chris Eliopoulos and David Aja

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

Page 10

Although speech bubbles remain blank for most of the issue, they can still change based on the different emphases given to the spoken words. For example, in this scene, Barney Barton’s speech bubble is spiky and sharp, which emulates the jagged nature of speech bubbles that usually feature shouting or an expletive. While his exact words are unknown at this point, the shape of the bubble in combination with Barney’s discontented facial expressions convey a sense of frustration from the character. A few panels later, his message is signed to Barton through the American Sign Language symbols for “WTF?”

Hawkeye, Vol. 4 #19, “The Stuff What Don’t Get Spoke,” July 30, 2014

Writer: Matt Fraction

Penciller and Inker: David Aja

Colorist: Matt Hollingsworth

Letterers: Chris Eliopoulos and David Aja

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

Page 10

Sound is modulated in Hawkeye #19 through varying font styles, as well. Because Clint Barton does not have complete hearing loss, characters can speak closely to him and he can understand some of what they are saying, just as Barney does in this scene. However, Clint’s hearing up close is still inconsistent, which is indicated through a new font that is more similar to an unfinished typed script than a piece of polished comic book dialogue. When Clint perceives these words, symbols such as question marks, hyphens, and parentheses capture the gaps in his understanding. The speech bubbles also change into waves and boxes to underscore the shift in how the dialogue is heard.

M.F.K., September 26, 2019

Author: Nilah Magruder

Publisher: Insight Comics

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

Page 20

M.F.K. is a fantasy-based graphic novel that follows a deaf girl named Abbie and her journey through a desert to spread her mother’s ashes. In this scene, Abbie has lost her hearing aid in a sandstorm and cannot hear. In the first few panels, the speech bubbles are blank to reflect her complete hearing loss. Later, when she places her hearing aid back in her ear, the sound is warped and patchy until she is able to once again perceive spoken words. This warped sound is visualized through wavy lines within a jagged speech bubble that gradually transforms into legible alphabetic words. Such a depiction mimics the scratchy and electrical sensation associated with putting in hearing aids.

A Silent Voice, “Chapter 51,” 2013

Author: Yoshitoki Oima

Publisher: Kodansha

Accessed from: Online Manga website “Mangakakalot”

Pages 52-53

In A Silent Voice, each of the main characters has a chapter dedicated to them that is told through their perspective, and Shoko’s chapter differs from the others because of her deafness. As a way of evoking the experience of being deaf, the visualization of the dialogue from the other characters is partially obscured, making the words somewhat illegible. This portrayal represents Shoko’s attempts to decipher what others are saying through her ability to lip-read. As a result, the audience is placed in her position of frustration and distress about not being able to fully understand, which creates empathy with her character and heightens the stress and anxiety of an intense moment in the manga.

Mooncakes, October 15, 2019

Author: Suzanne Walker

Illustrator: Wendy Xu

Publisher: Oni Press

Accessed from: Hoopla Digital

Page 92

Mooncakes is a graphic novel about two teenagers, Nova, who is a witch and is deaf, and Tam, who is a werewolf, living in a world of magic. In these panels, the story explores Nova’s deafness. She wears hearing aids, which she uses in this scene to listen to a conversation in her kitchen. Her act of increasing the range of her hearing aids is visually depicted through a standard pictorial representation of volume increases. In addition, while Nova does have a hearing disability, her deafness does not define her character; instead, the novel explores all facets of her personality, including her relationship with her parents, who are ghosts, her budding romance with Tam, and her strengthening magical powers.

Daredevil: The Man Without Fear #51, “Echo: Part 1,” November 2003

Writer, Artist, and Colorist: David Mack

Letterer: Cory Petit

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Page 28

Maya’s interpretation of sound comes through her perception of images; as a result, narratives told from her perspective modulate sound into artistic visual expressions that reflect her impressions of how a sound is perceived by herself and others. In this panel, one such artistic visualization is represented. Maya reflects on her perspective of color through an allusion to Pablo Picasso, positing that “color must be what sound is like if you can hear.” She also reinforces the idea that these images help her imagination conjure ideas of sound, offering that “some painters know how to put the colors together just the right way, so that I imagine it is like music.”

Visual Impairment and Audio-Based Comics

For those with visual impairments, such as blindness, audio-translated versions of comics offer an alternative way to experience this visually-dominant medium. One of the most popular access points for these types of comics is GraphicAudio, which transforms comics into audiobooks that include audible sound effects, voice actors, and background music. Such additions provide necessary context that allows those with visual impairments to receive the full experience of characterization, environment, and action that would be lost with strict narration and dialogue.

At the same time, there are noticeable differences between the audio and visual formats of these stories. For instance, compare the visual version of Archie, Volume 4 to its aural counterpart. In the one from GraphicAudio, external characters, such as the waiters, are given speaking lines and distinct character voices, both of which are not found in the visual version. Likewise, the narrator adds additional context to the scenes by adding commentary on the inner thoughts of Archie and Veronica, and while their sentiments can be inferred through the facial expressions of the characters in the visual form, they are not stated outright like in the aural form. These ideas are also found in Archie, Vol. 5, which features Archie and Veronica on a golf course. In order to establish the setting, an ambient soundtrack of gurgling water and duck noises is added to the audio version. Interestingly, entire plot points are also changed in this section of the novel, with the visual form featuring a visual joke of Archie talking to Veronica while trying to hit a ball while waist-high in water, and the audio one featuring the same conversation as they drive the golf cart. Such a change could be due to the fact that trying to translate the visual joke would lose some of its humor by over-complicating the narrative.

Archie Vol. 4 (Visual), 2021

Story by: Mark Waid

Art by: Pete Woods

Letterer: Jack Morelli

Publisher: Jon Goldwater

Pages 15-17

“GraphicAudio,” Archie, Vol. 4

Archie Vol. 4 (audio), 2021

Release date: 2021

Director and Narrator: Bradley Foster Smith

Starring: Robb Moreira as Archie and Laura Harris as Veronica

Sound Designers: Michael Hanusiak

Producers: Richard Rohan, Duane Beeman, and Matt Webb

Executive Producer: Anji Cornette

Pages 15-17

Archie Vol. 5 (Visual), 2018

Story By: Mark Waid

Art By: Audrey Mok

Colors by: Kelly Fitzpatrick

Letterer: Jack Morelli

Pages 52-55

“GraphicAudio,” Archie, Vol. 5

Archie Vol. 5 (audio), 2022

Director and Narrator: Bradley Foster Smith

Starring: Robb Moreira as Archie and Laura Harris as Veronica

Sound Designers: Michael Hanusiak

Producers: Richard Rohan, Duane Beeman, and Matt Webb

Executive Producer: Anji Cornette

Pages 52-55

Access the GraphicAudio website to explore other audio versions of comics that are offered.