Culture

Just as certain sound effects have come to define comics within popular culture, popular culture shapes sound in comics. To understand a sound, one must first have a cultural understanding of its real-world diegetic equivalent in order to have a reference point for how the sound fits into the narrative. Factors such as the language of origin for the comic and the cultural trends within that nation at the time of its development influence the decision of the comic creators, as well as the impact of the sound on the audience.

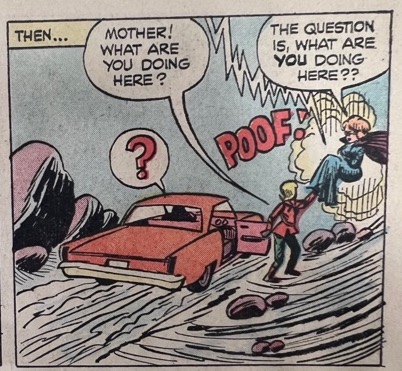

Bewitched #5, June 1966

Publisher: Dell Publishing Company

Page 5

In both television and comic adaptation, Bewitched is a culturally significant piece of media. The themes of gender, magic, and American familial norms that permeate this series have led to its prominent placement in 20th-century popular culture. The magical abilities of the main character, Sam, define the story, and she is known today as one of the most popular depictions of a witch in entertainment. As a result, the “Poof!” sound illustrated within a bubble of smoke and lightning both in this panels and throughout the comic act as more than just a signifier of her magic in use; the onomatopoeia adopts a metonymic quality that represents her status as an iconic witch in popular culture. Indeed, the “Poof!” sound has become synonymous with Sam, the television show, and the idea of magical abilities in general, causing it to take on more cultural meaning than just a visual indication of a sound.

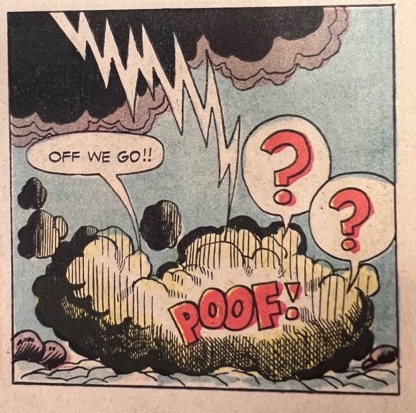

Plop #20, “Meat His Maker; Plopular Poetry; Super Plops; The Gentle Way; Monster Plops; Prison Plops,” April 1976

Writer: Steve Skeates, Wally Wood, and Maxine Fabe

Artist: David Manak, Sergio Aragones, and Wally Wood

Penciller: Don Edwing

Publisher: DC Comics

Page 31

While this page from Plop features several different sound effects, the “PLOP” is the most prominent due to its explosive visual style and being the name of the comic. As the narrative surrounding the sound indicates, the comic is often self-referential and pokes fun at comics. In the story, the “PLOP” is used to bury miners that are looking for jokes for the comics because the jokes are terrible. Ironically, the jokes that they are looking for are used within the Plop comic series, which is their way of poking fun at both the series and funny page comics in general by suggesting that they possess unfunny jokes. Such a story relies on cultural awareness of common onomatopoeia and its usage in comics in order to subvert their visual norms for comedic value.

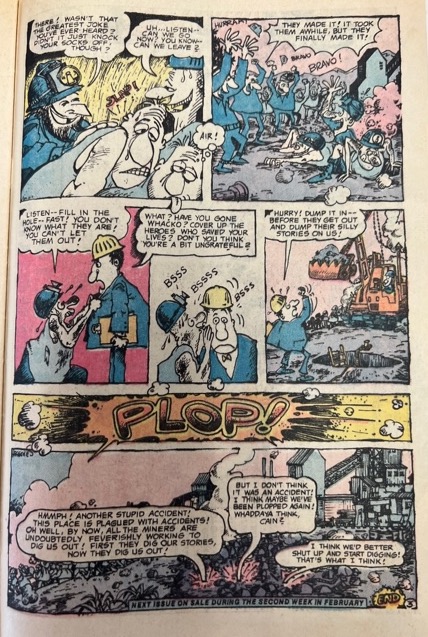

Batman: The Killing Joke #1HC-A, May 2008

Writer: Alan Moore

Artist and Colorist: Brian Bolland

Letterer: Richard Starkings

Publisher: DC Comics

Page 44

This panel plays off of the cultural expectations of the flow of a comic book. In this final showdown between Batman and the Joker in Batman: The Killing Joke, Batman appears to be cornered and defenseless. Joker pulls a gun on him, and the audience expects that the next panel will be an image of him shooting Batman with the “CLICK” onomatopoeia to indicate the action of the Joker pulling the trigger. However, the gun is revealed to be a joke gun that produces a flag with the word “CLICK” on it. The composition of the page, with its sound effect-centric format and the action blurs in the foreground, parodies the traditional superhero comic style of aggressive and intense fight sequences, resulting in a plot twist for the audience that is also in character for the tricky nature of the Joker. Such a plot twist depends on the audiences’ cultural understanding of conventional comic book flow and then goes against those expectations at a moment of high suspense.

Translation

Translation in any context requires consideration of linguistic and cultural aspects of the text. With reference to comics and, in particular, onomatopoeia, the phonetics of the words must also be considered. As the comics in this section suggest, some translations adhere more closely to the style of the language of origin, while others shift in order to meet the needs of the new language and audience. These translated comics feature both European comics and Japanese manga.

Manga

Manga as a whole differs from European or American comics because the integration of sounds is much more atmospheric. Evidence of this contrast comes from the division of onomatopoeia types into two categories within Japanese language: giongo and gitaigo (Pratha et. al. 100). Giongo refers to “hearable” or diegetic sounds, and are words that mimic the sound that they embody; these types of words are akin to onomatopoeia in English and Romance languages. Gitaigo, however, is unlike these Romance language words because it describes the sound as a state of being. Such words are defined as “state-mimicking words,” and examples include the state of worry or the state of sparkling. Gitaigo, therefore, demonstrates that sounds in manga encapsulate more than just that which is hearable, but also the tension, emotions, and atmosphere of a scene.

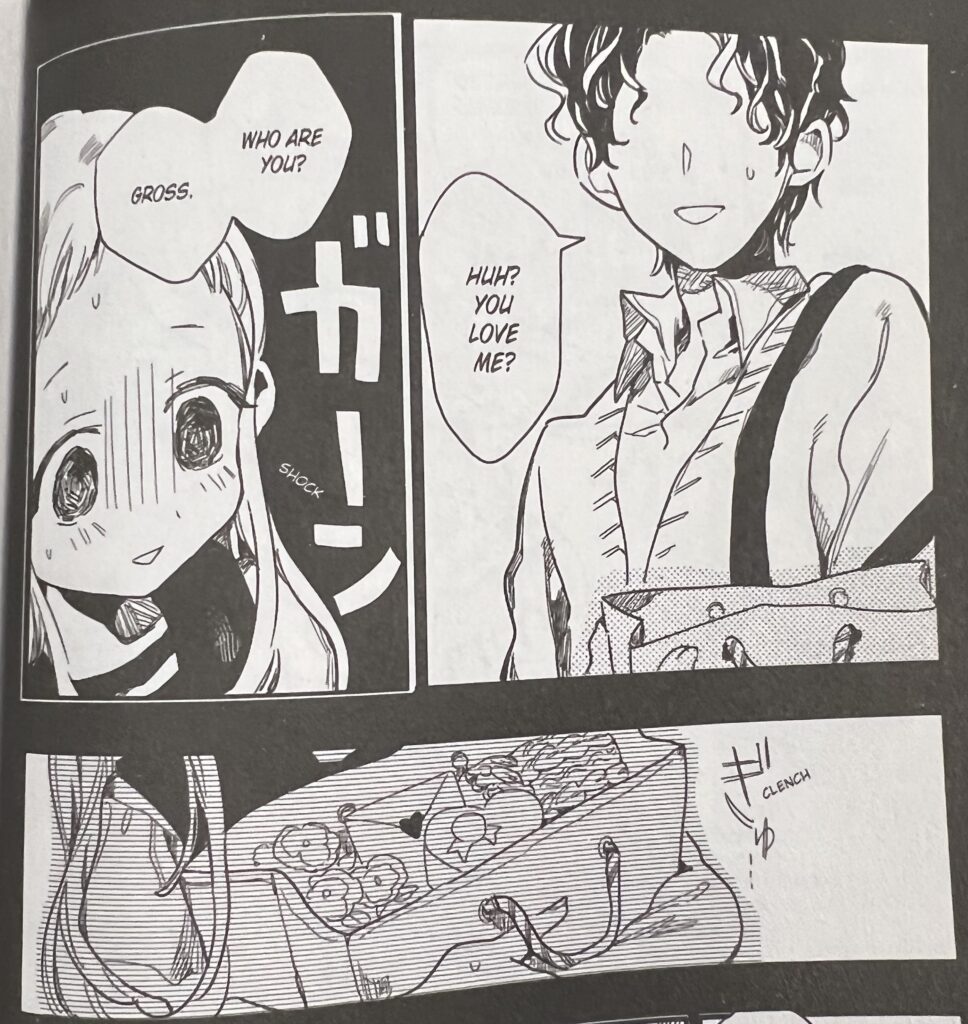

Toilet-Bound Hanako-Kun #1, 2017

Author: Aidalro

Translator: Alethea Nibley and Athena Nibley

Letterer: Jesse Moriarty and Tania Biswas

Publisher: Yen Press

Page 14

This series of panels exemplify the concepts of Giongo and Gitaigo in Japanese Manga, both of which are distinct to that nation’s narrative culture and style. In the first panel, the female character experiences a condition of “shock” which is emoted through the Japanese script floating next to her. While shock in and of itself does not possess a singular sound, the state of being associated with it is described through the term, thus categorizing it as a Gitaigo. A few panels later, that same character “clenches” her purse close to her body, and such a sound is demarcated in the script above the English translation. Since the action reflected by this word is hearable, it is a Giongo.

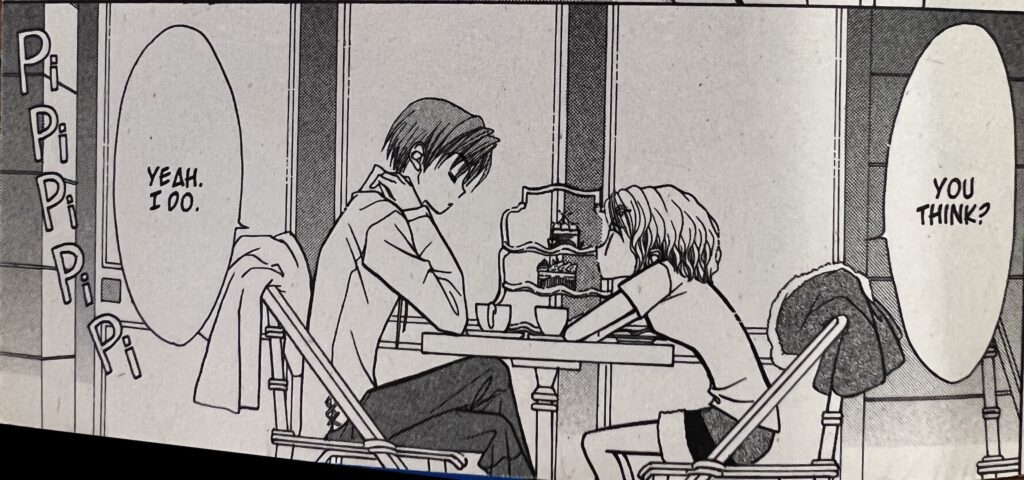

Gals Vol. 4, 1998

Author: Minoan Fujii

Translation: Sheldon Drzka

Adaptation: Johnathan Tarbox

Lettering: Saida Temofonte

Publisher: SHUEISHA Incorporated and DC Comics

Page 24

The Japanese sound for a telephone is not “RING” as it is in English but rather “Pi pi pi.” Such a sound is found in this panel from the Japanese manga Gals, Vol. 4. While both evoke the sense of a constant notification sound, they can have different ways of indicating their duration. For the Japanese term, the number of “Pi” noises suggests the length of the telephone notification, while for an American comic, duration can be indicated by either the length of the letters within the word “RING” (“RING” vs “RIIING”) or the number of times the word is included on the page.

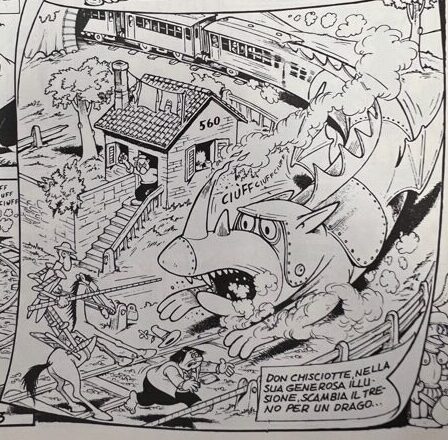

Il Mago: La Rivista Dei Fumetti E Dell’umorismo #13, “Asterix E L’Indovino,” April 1973

Page 37

This page in an Italian comic book of a story about Don Quixote illustrates the idea that translators take onomatopoeia into consideration when adapting the comic. On this page, the train produces a “Ciuff ciuff ciuff” sound because it is the Italian onomatopoeia for train noises, as opposed to the “chuga-chuga” and “Choo-choo” of English or “tchou tchou” of French (which is the original language of the comic). This translated sound demonstrates that while the meaning of translated words can remain the same, their phonetics can change to meet cultural expectations and norms.

View More Examples of Translation

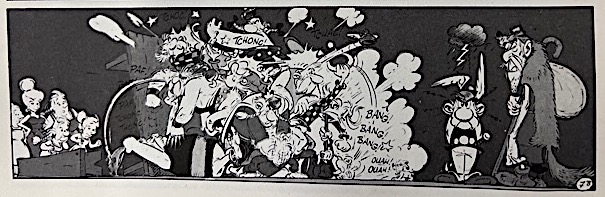

Il Mago: La Rivista Dei Fumetti E Dell’umorismo #13, “Asterix E L’Indovino,” April 1973

Page 6

While the chaos of this scene from the Italian-translated version of the French comic strip Asterix is the main focus of the panel, there is a small figure at the bottom that is much more intriguing from a translated onomatopoetic standpoint. This figure is the dog Dogmatix, who is drawn with the sound “Ouah! Ouah!” shooting from his mouth, which is the French sound effect for a dog bark. Such a depiction is significant because the comic is written in Italian, but the sound remains in its original language. Leaving the onomatopoeia in its original language contrasts with the other sound effects in the comic because they have been translated into Italian or English, as evidenced by the “BANG!” found directly above the dog bark. Whether the mistranslation is an oversight or intentional, it nevertheless demonstrates the fact that sound effects can be culturally specific and vary from language to language.

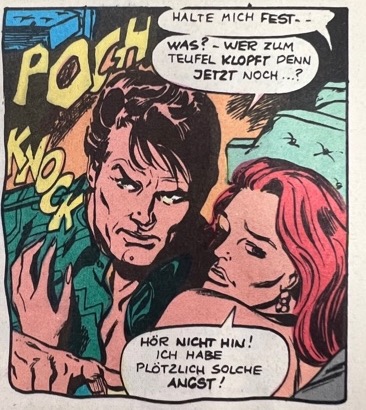

Die Gruft von Graf Dracula #15, “Wie Lange Isa Erin Vampier tot?”

Page 27

This comic is a German translation of an American horror comic, as evidenced by the German speech bubbles on the right-hand side of this panel. The sound effects featured in this panel are “KNOCK” and “POCH,” which is the German word for knocking at the door. While the words vary in language, the artist has elected to maintain the font, colors, and style of the two sounds, which suggests that a significant aspect of the impact of the term on the audience is not just the word itself but also its visual components. In this case, the scraggly formatting of both “POCH” and “KNOCK” is jarring, which reflects the abrupt sound of someone banging on the door.

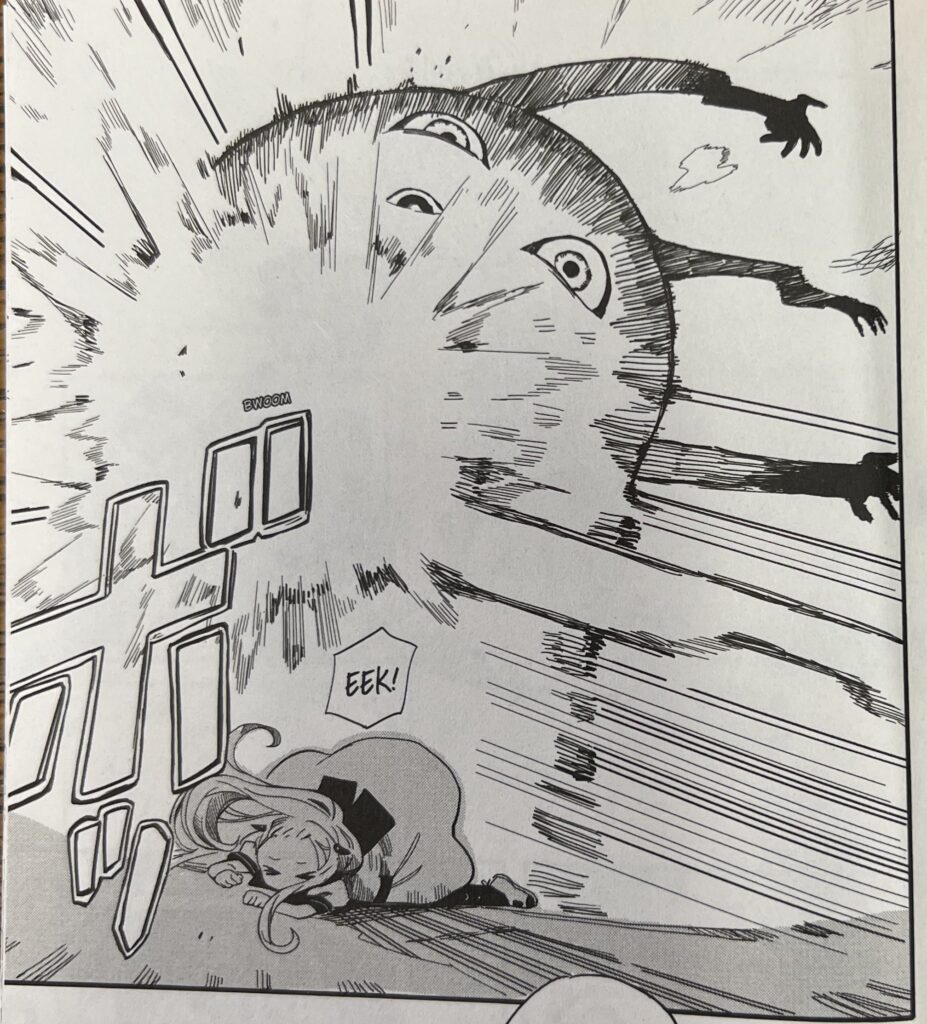

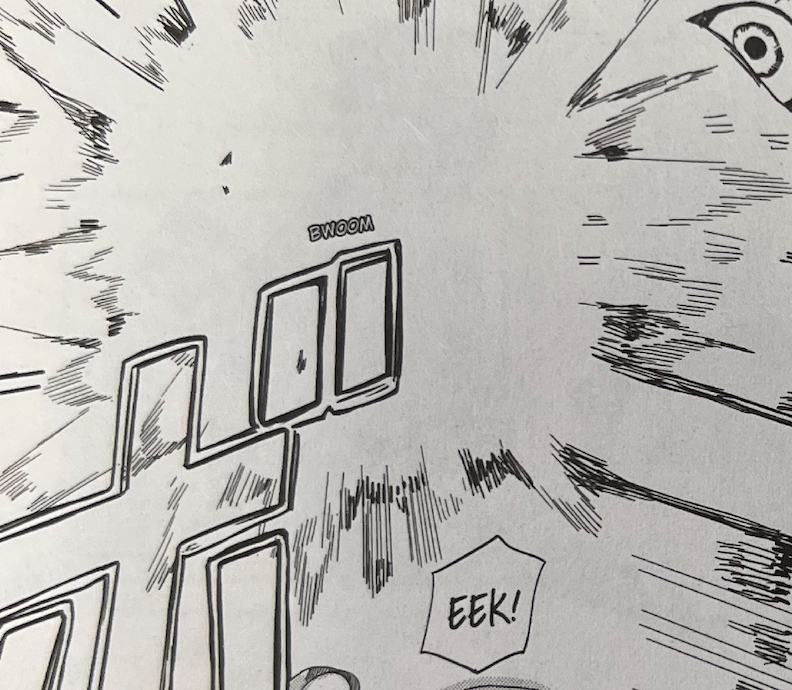

Toilet-Bound Hanako-Kun #1, 2017

Author: Aidalro

Translators: Alethea Nibley and Athena Nibley

Letterers: Jesse Moriarty and Tania Biswas

Publisher: Yen Press

Page 75

Toilet-Bound Hanako-Kun adopts a translation style that highlights the original Japanese script. In this panel, the Japanese term “BWOOM” retains its Japanese lettering style, font, and sizing. Therefore, in order to convey the translation, the English subtitle is written in a smaller font above the original sound effect. The result of this translation technique is a fascinating juxtaposition of the dynamism of the Japanese script and the hidden, near illegibility of the English translation. The effect of such a choice could depend on the preferred language of the audience. For English readers, the impact could be lessened because their eye is drawn to the diminutive font over the expressiveness of the original text. For Japanese readers, the technique could be more effective because they might appreciate the fact that it retains the intentional artistry and formatting of the manga.

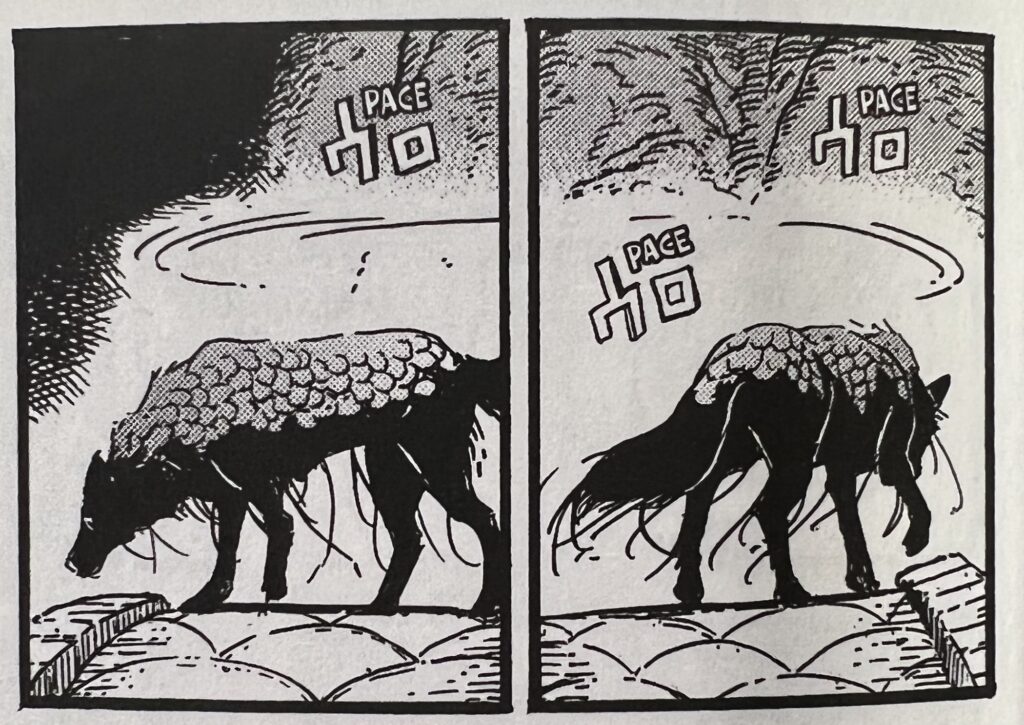

Witch Hat Atelier 5, 2019

Author: Kamome Shirahama

Translator: Stephen Kohler

Letterer: Lys Blakeslee

Publisher: Kiichiro Sugawara

Page 39

This manga adopts a translation style that more closely unites the original Japanese script with English subtitles when compared to Toilet-Bound Hanako-Kun. The English translations adopt the same font and physical features as the Japanese terms, with “PACE” possessing thick and blocky characteristics and “STAGGER” possessing wavy and muddled characteristics. The result of such a translation choice is that the English subtitles reflect the visual impacts of the Japanese script more similarly than in other English-translated manga but at the expense of the intrusiveness of the English terms within the formatting of each panel.