Sound effects are perhaps the most well-known forms of sound found in comics. The words “POW!” and “ZAP!” are synonymous with comic book heroes, and the distinct visual style of these sound effects has come to define comic books as a medium. Another word for sound effects is “onomatopoeia,” which are words that mean and are spelled to mimic the word that they define. As with music, onomatopoeia in comics serves the character and environment of the story. Because sound effects as a category is so broad in style and purpose, the following sections delve into different frames through which to organize and examine these types of sounds

Explore Style, Environment, and Characterization

Explore Culture

Style

Style relates to both the style of the comic and the style of the onomatopoeia. In terms of the comic, the font, coloring, and sizing of these words depend on the genre of the comic, and creators style their onomatopoeia to be in alignment with these genres. For instance, a large, flashy, and brightly colored “POW” would feel out of place in a monochromatic noir comic. In terms of onomatopoeia style, these words can embody two types of sound: movement or impact. Movement words include “SLASH” and “WHIZ,” which convey the movement of an object through space or the action that an object or figure undertakes. The impact is the sound of the object hitting another object, such as “WHAM” or “BAM.” While motion blurs and action lines accompany the style of movement words, explosive visuals such as bursts of light color accompany the style of impact words.

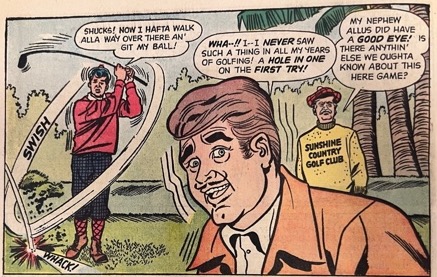

The Beverly Hillbillies #4, March 1964

Publisher: Dell Publishing Corporation

Page 6

This panel of The Beverly Hillbillies playing golf exemplifies the idea of categorizing sound effects into movement and action versus impact. The “SWISH” of the club contrasts with the “WHACK!” of hitting the ball. In this instance, the swish is the movement sound because it mimics the whoosh of a club moving in the air. The motion lines reinforce the presence of movement sounds because they demonstrate the show the arc of the club’s swing. Likewise, the whack effect is the impact sound because it imitates the sound of a ball being struck forcefully by a club and is surrounded by explosive lines, which is also common to depictions of impacts.

View More Examples of Style Types

Spider-Man: Die Spinne, “Wer Ist Der Neue Koenig Der Unterwelt?”, October 1998

Publisher: Marvel Deutschland

Page 14

This series of four panels exhibit the conventional styles of superhero style onomatopoeiae and augment the action of the scene. In terms of the superhero comic style, the “PTOOM” of the first panel is drawn with a red gradient and bolded letters that break through the gutters, both of which are common to superhero comics. The onomatopoeiae also demonstrate the intensity of the action, which is, in this case, a car crash. When displayed in this sequence, the three onomatopoeia indicate the different aspects of the crash by adding context to the zoomed-in images of each panel. For instance, the close visual proximity of the tire on the pavement is reinforced by the “SCREE” of the wheels, which, when put together, suggest to the readers that the car came to an abrupt stop.

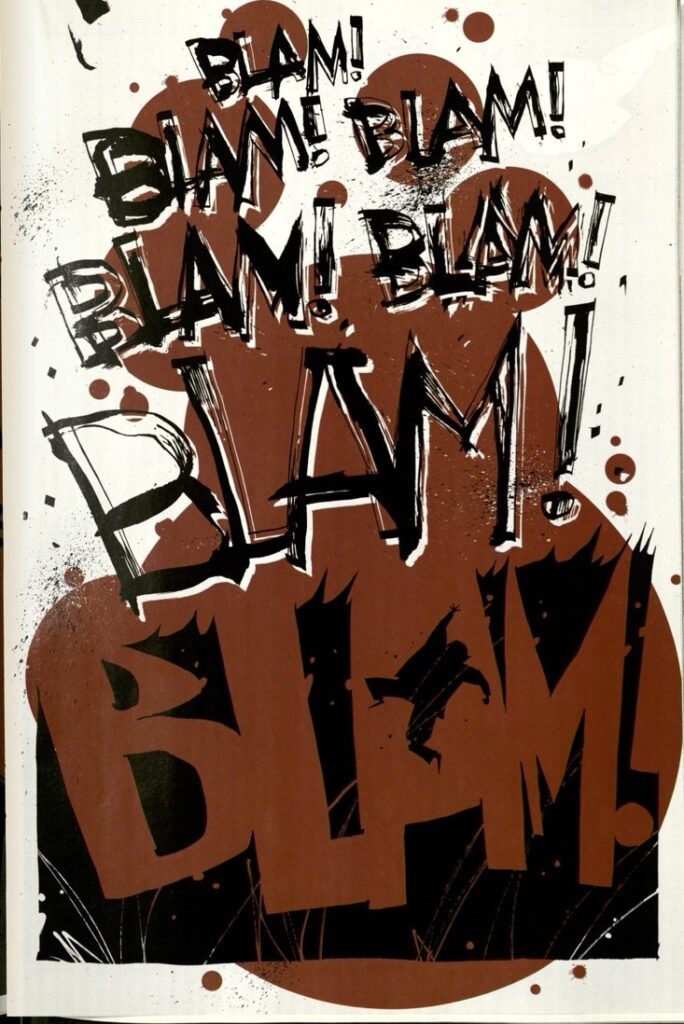

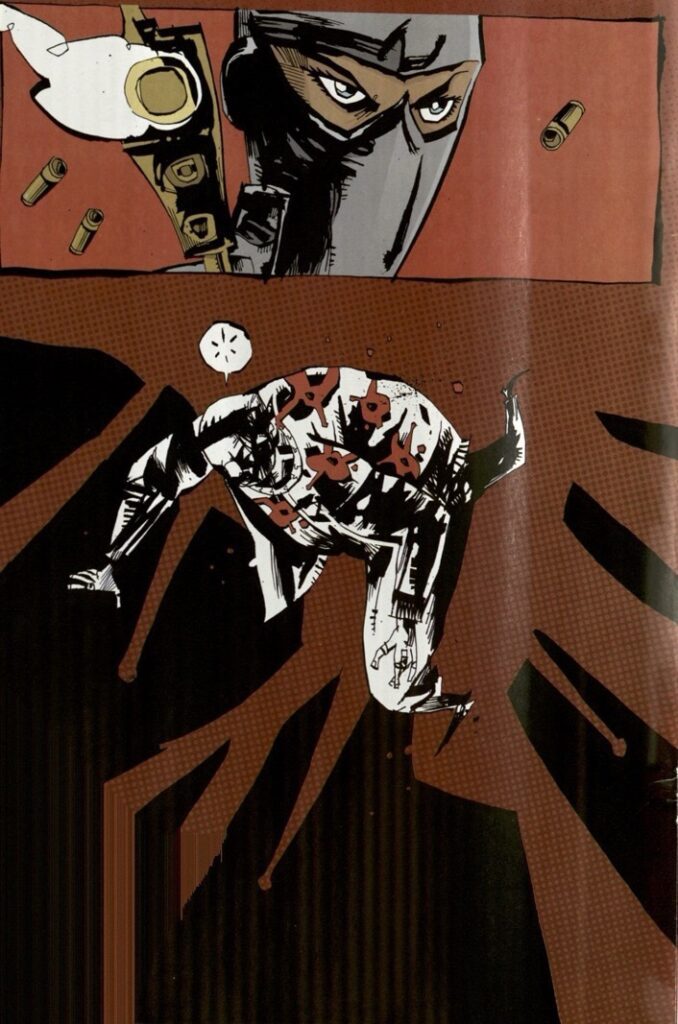

Kick Drum Comix #1, “Death of the Popmaster/Coltrane’s Reed,” September 2008

Page 24

In the story preceding this splash page, “Popmaster,” a gang leader, walks around confident in his defeat of other rivals and gangs. However, unbeknownst to him, an assassin is preparing to kill him. The culmination of these two storylines is the assassin shooting Popmaster multiple times, as evidenced by the repeated “BLAM!” onomatopoeia on the first page. The jagged, scratchy font of the words reflects the gritty punk genre of the rest of the comic, and the red coloring that seeps down the page evokes the idea of seeping blood. Overall, the grungy style of the comic is maintained in this high-intensity moment through these specific visual decisions. A unique feature of this page is that while most comics integrate the sound effects into the other parts of the panel, such as the landscape and figures, the first page instead integrates the figures into the words, with the body of Popmaster sprawling in such a way that it creates the gap in the letter “A” of the final “BLAM!” The second page displays the result of this violent confrontation, with Popmaster falling to the ground with multiple gunshot wounds.

Demon Slayer: Kimetsu No Yaiba Volume 13, 2016

Artist and Story by: Koyoharu Gotouge

Translator: John Werry

Touch-up and Letterer: John Hunt

Designer: Jimmy Presler

Publisher: VIZ Media

Page 13

Similar to American and European comics, Japanese Manga distinguishes between the sound of impacts and the sound of action. This page features both of these categories in the midst of an action-heavy sequence. The terms “WHOK” and “FWAM” evoke the sound of the main character Tanjiro hitting the ground after falling from a tree. Such sounds are reinforced with the inclusion of explosive impact lines that emulate an explosion or jagged speech bubble. Likewise, the onomatopoeia “FLIP” is the sound of that same character flipping mid-air and losing his sword as he falls, and it exemplifies the sound of movement. Motion lines in the shape of the weapon’s arc are once again present to bolster the notion of sound in the scene.

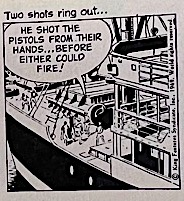

The Official Secret Agent #1, June 1988

Writer: Archie Goodwin

Artist: Stanley Pitt and Al Williamson

Publisher: Pioneer Comics

Page 4

Within some comic genres, creators avoid using sound effects altogether. This fight sequence on a boat from “The Official Secret Agent,” which is drawn in a noir and spy thriller style, features the phrase “Two shots ring out…” instead of an onomatopoeia of a gunshot such as “Bang!” This style is dialogue and narrative-centric, so including an onomatopoeia would disrupt the stylistic flow of the comic. Many other comics within this spy thriller genre utilize similar descriptions, as opposed to visualizations, of sound, as well.

Environment

As with music, sound effects can dictate the environment of the comic both physically and temporally. A defining feature of the interaction between sound effects and time in comics is the phonetic length of the onomatopoeia. The number of repeated letters within a word conveys to audiences the duration of the sound. For example, the length of the sound of a car horn could be indicated as fast (“BEEP”) or slow (“BEEEEEP”) depending on the number of “E’s” in the onomatopoeia. At the same time, the font size of a word suggests the physical distance between the sound and the object from which it derives.

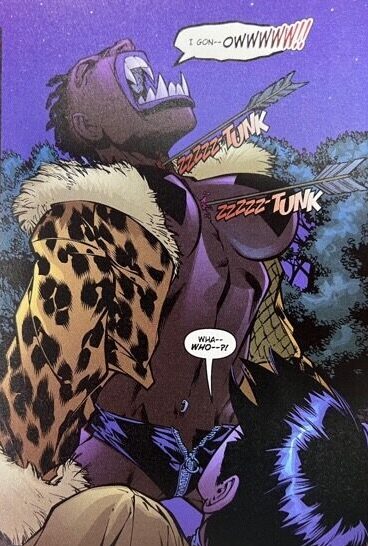

Crimson #3A, “Payment in Blood,” July 1998

Writer: Brian Augustyn

Plotter: Francisco Gerardo Hagenbeckm Humberto Ramos, Oscar Pinto

Penciller: Humberto Ramos

Inker: Sandra Hope and Chris Elarmo

Colorist: Alex Bleyaert, Ian Hannin, and Bad@ss

Publisher: Image Comics

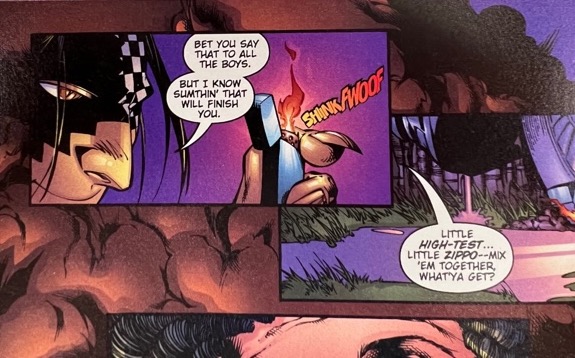

Page 26

The sound of an arrow hitting this character’s chest demonstrates the divergence between sound and visuals in relation to time, as well as the need for the audience to contextualize and infer moments of action that are not depicted. While the arrow flew through the air and pierced this character, such moves are not shown. Instead, the impact of the hit and the sound of a “zzzzz-TUNK” express these missing moments. The “zzzzz” represents the arrow flying through the air, while the “TUNK,” which is larger in font size and separated with a hyphen, mimics the sound of the arrow hitting their chest. As a result, the sound effect illustrates two separate events that occur over the course of several seconds. Thus, even though the other components of the story have experienced a jump forward in time, such sound effects fill in these gaps, allowing audiences to more fully grasp the events in the scene.

Crimson #3A, “Payment in Blood,” July 1998

Writer: Brian Augustyn

Plotter: Francisco Gerardo Hagenbeckm Humberto Ramos, Oscar Pinto

Penciller: Humberto Ramos

Inker: Sandra Hope and Chris Elarmo

Colorists: Alex Bleyaert, Ian Hannin, and Bad@ss

Publisher: Image Comics

Page 2

This panel demonstrates two prominent techniques for incorporating onomatopoeia into a physical environment. The “VVRRRRMMMMM” of the car flying through the window demonstrates the most common style, which is imposing the text over the scene in a way that augments the actions and impacts of the objects around it without distracting from the object itself. In contrast, the “SKLEEESSH” of the glass breaking is semi-transparent and blends in with the setting, which mimics the texture and fragility of the object and background that it represents. Such a style is often used in environments that involve water or smoke because these atmospheres possess similar delicate and impermanent qualities of breaking glass.

View More Examples of Environment

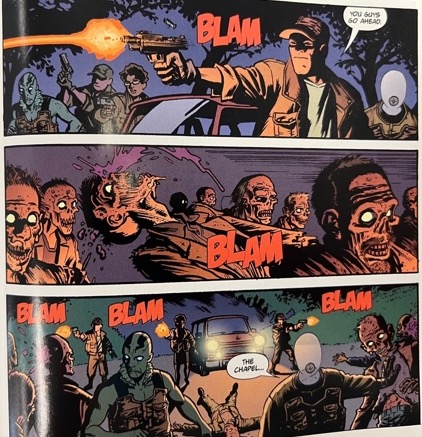

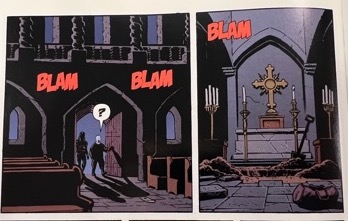

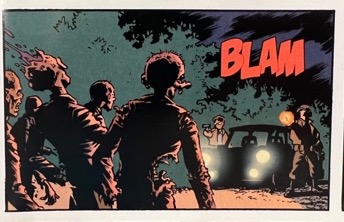

Hellboy: 20th Anniversary Sampler, “Another Day at the Office,” March 19, 2014

Writer: Michael Mignola and R. Sikoryak

Artist: Fabio Moon, Michael Mignola, R. Sikoryak, and Cameron Stewart

Colorists: Michelle Madsen and Dave Stewart

Letterer: Michael Hensley and Clem Robins

Publisher: Dark Horse Comics

Page 27-29

These panels from “Another Day at the Office” feature the sound “BLAM” as the protagonists shoot zombies with their guns. The “BLAMs” vary in size and frequency but are all relatively large and prominent in the first few panels. Then, as the protagonists move to other locations, the sound effect becomes less frequent and smaller in font, indicating that the figures are moving farther away from the action. Then, when they return to the scene, the sound effects correspondingly reappear. The sound therefore establishes the physical landscape of the story because it is a visualized aural indicator of the size, layout, and timeframe of the scene. It acts as a reference point from which the readers can infer the setting around the characters.

Crimson #3A, “Payment in Blood,” July 1998

Writer: Brian Augustyn

Plotter: Francisco Gerardo Hagenbeckm Humberto Ramos, Oscar Pinto

Penciller: Humberto Ramos

Inker: Sandra Hope and Chris Elarmo

Colorists: Alex Bleyaert, Ian Hannin, and Bad@$$

Publisher: Image Comics

Page 25

The onomatopoeia featured in this panel is “shink-fwoof,” which is the sound of a sparking lighter. Such a sound embodies the notion of warped time in comics. The act of lighter sparking takes several moments, but those moments are captured in a single panel; therefore, the passage of time is indicated through the length of the word and its shift in formatting. When the word changes from “shink” to “fwoof,” the second part of the word is italicized and adopts a darker red hue when compared to the pale yellow of the beginning of the word. These transitions in font style and color mimic the yellow spark of trying to start a lighter followed by the presence of fire once the spark has caught. As a result, the word symbolizes and differentiates between two separate acts across a period of time while still existing within one visual moment.

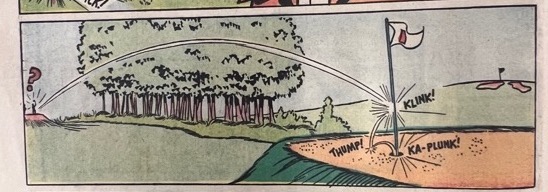

The Beverly Hillbillies #4, March 1964

Publisher: Dell Publishing Corporation

Page 6

In this scene, the Beverly Hillbillies play a round of golf, and this panel features three onomatopoeia: the “KLINK” of the ball hitting the poll, the “THUMP” of the ball hitting the ground, and finally the “KA-PLUNK” of the ball landing in the hole. The sounds augment the motion lines of the ball in order to illustrate the progression of time. The differentiation between sounds reinforces such augmentation. Each impact sound possesses a distinct sound, which clarifies to the audience that multiple moments have occurred over the course of several seconds between the ball leaving the tee and landing on the green. Such an example of the complication of time in comics embodies the ideas of American Comics scholar Scott McCloud, who argues that “words introduce time by representing that which can only exist in time – sound” (Page 95, Understanding Comics). In other words, because sound can only exist within a temporal setting, the introduction of onomatopoeia into a story provides that scene with a sense of forward progression, even if the background and other visuals appear stagnant.

Characterization

Sound effects characterize both people and objects in a narrative. Some sounds, such as Wolverine’s “SNIK,” are so integral to a character that they are now culturally interchangeable with them. Some objects also possess signature sounds that define them. These sounds can advance the plot because they heighten the contrast between the object of narrative significance and all other objects in the story.

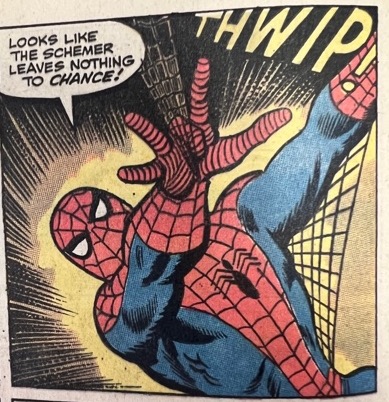

The Amazing Spider-Man, Vol. 1 #84, “The Kingpin Strikes Back,” April 30, 1970

Writer: Stan Lee

Penciller: John Romita Sr. And John Buscema

Inker: Jim Mooney

Letterer: Sam Rosen

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Page 14

For Spider-Man, the “THWIP” sound of the webs is as synonymous with the character as the red and black mask and the spider logo on the chest. The sound, which expresses the action of the webs as opposed to their impact, has become to symbolize the character. In fact, even though this panel features the onomatopoeia as slightly out of focus, the sound is nevertheless easily recognizable and audiences can quickly make an association with the sound and the image of Spider-Man flying from building to building. It is now an iconic sound that has its roots in the original creation of this web-slinging superhero.

View More Examples of Characterization

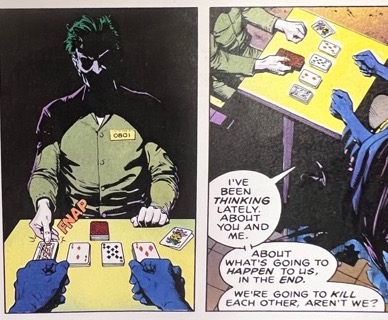

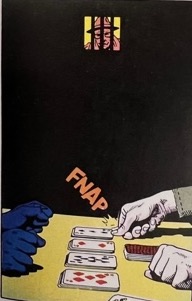

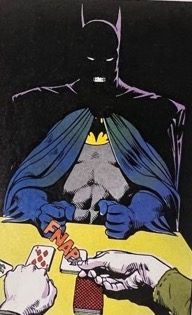

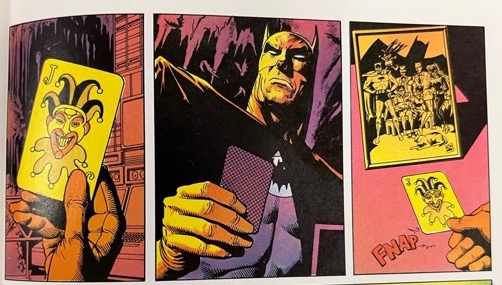

Batman: The Killing Joke #1HC-A, May 2008

Writer: Alan Moore

Artist and Colorist: Brian Bolland

Letterer: Richard Starkings

Publisher: DC Comics

Pages 4-5 and 11

While relatively small compared to the format of the rest of the panels, the “FNAP” sound of the Joker placing a card plays a central role in characterizing this infamous Batman villain. Cards and card games symbolize his trickiness, especially the face card of the Joker in a standard 52-card deck. Thus, depicting the Joker as sorting through cards with this sound effect reminds audiences of these aspects of his character. In addition, the sound is repeated over several panels, which sets a visual rhythm of the story and sets a pace for the intense conversation between the Joker and Batman. The sound effect as a visual metonymy for the Joker is epitomized in the last series of panels when Batman discovers a joker playing card at a crime scene and places it on a table with a familiar “FNAP” that recalls the sound, character, and scene from a few pages prior.

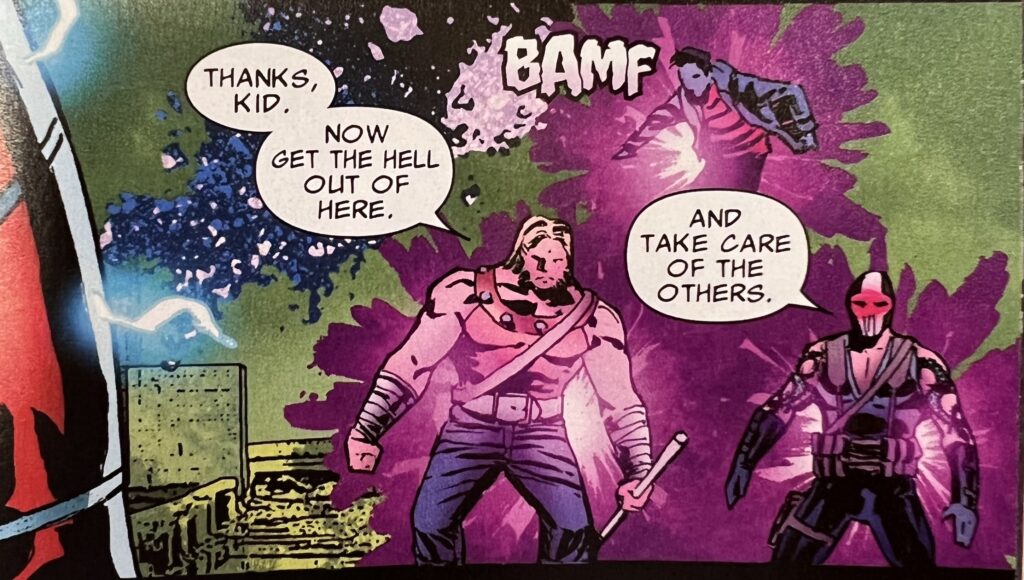

Astonishing X-Men, Vol. 3, “X-Termination – Part Two,” March 27, 2013

Writer: Gregory Pak, David Lapham, and Marjorie Liu

Penciller: Matteo Buffagni

Inker: Renato Arlem

Colorist: Chris Sotomayor

Letterer: Joe Caramagna

Publisher: Marvel Comics

Pages 6 and 25

The “BAMF” sound of Nightcrawler’s mutant abilities has come to define this member of the X-Men. This sound effect accompanies the act of Nightcrawler teleporting away from the scene; likewise, it represents the character in a similar way to Spider-Man’s iconic “THWIP” because only they can elicit such an ability-dependent sound. Characters within the X-Men universe also recognize the uniqueness of the sound. As comics scholar Anna Peppard illustrates, the onomatopoeia is “often treated self-reflexively” in that characters sometimes ask Nightcrawler to “bamf them up there,” which suggests that the sound is so distinct and frequent in its association with Nightcrawler that it has transformed into a verb used specifically for him within the world of the comic. Dr. Peppard also explains that “BAMF” has taken on additional meanings throughout the course of the X-Men series. A prime example of this change is the sound effect evolving to signify a race of beings called the “Bamfs” from another dimension that later became a group of loyal helpers to Nightcrawler.

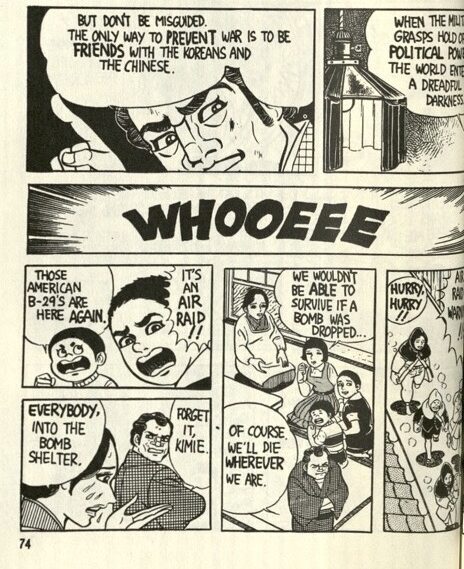

Barefoot Gen, 1987

Author: Kenji Nakazawa

Translation by: Project Gen

Page 74

In addition to the figures in a comic, onomatopoeia can characterize objects. Such a notion is especially true if the object holds significance to the plot or possesses a deeper symbolic meaning within the narrative. For instance, the air raid horn sound in Barefoot Gen, a graphic novel about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II, is represented with a “WHOOEEE” sound that informs the Japanese citizens of an incoming bombing strike. The raid horn has a unique spelling that differs from the sound of explosions or other sirens, and the fact that few other effects are given a panel solely dedicated to them exacerbates this difference in sound. The differentiating and singularizing of this term could serve to foreshadow the tragic events at the end of the novel when the atomic bomb is dropped on the two Japanese cities that killed hundreds of thousands of citizens.

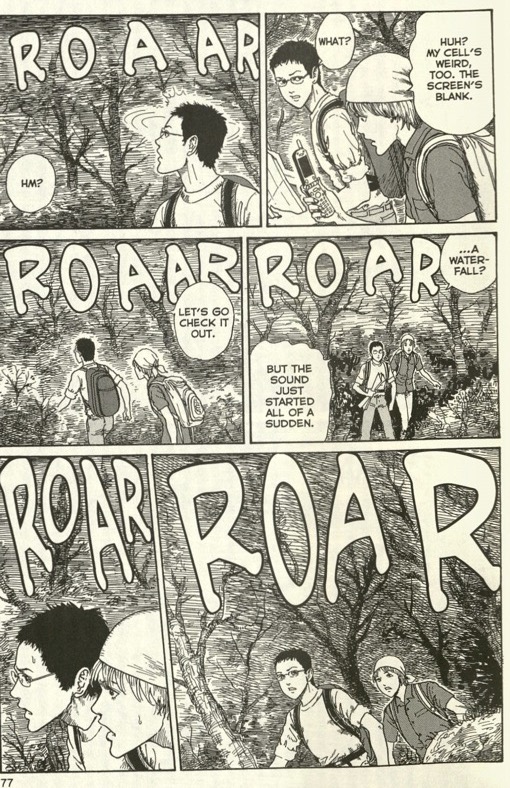

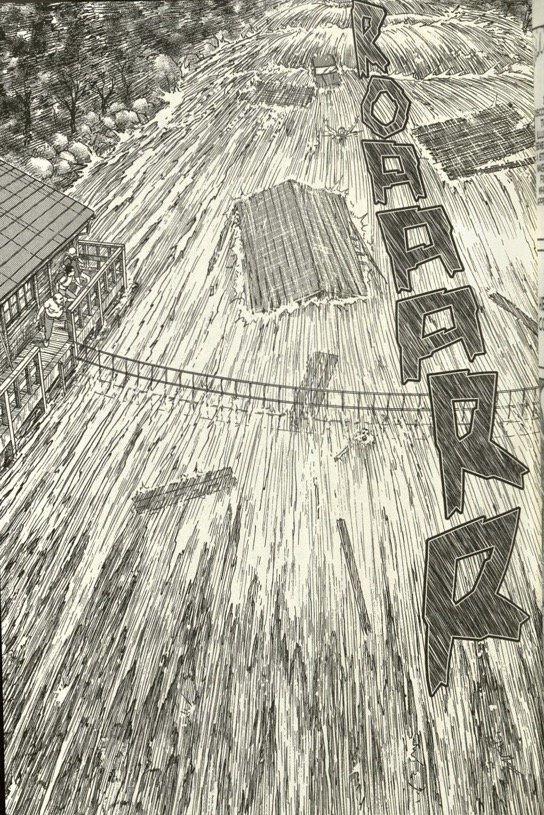

Smashed: Junji Ito Story Collection, “Roar,” 2019

Author: Junji Ito

Publisher: VIZ Media

Pages 77 and 98

Smashed is a collection of horror manga that features monsters and other frightful creatures. In “Roar,” the two main characters hear a “ROAR” noise that disturbs them, so they decide to investigate. As they get nearer to the source, they discover that the roar emanates from a ghost flood that terrorizes a remote mountain pass. The sound of the “ROAR” comes to characterize the flood and all of the atrocities associated with it. The selection of the onomatopoeia “ROAR” is of particular significance because it contributes to a zoomorphic quality of the flood in which the water expresses the sounds of an animal, in this case, the roar of a beast or monster. The “ROAR” reaches its crescendo on the final splash page when the full force of the flood is shown alongside an elongated and serrated version of the sound effect.